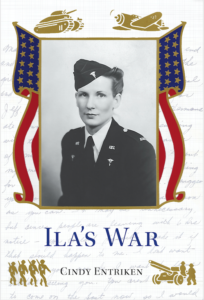

Ila graduated from the three-year nursing program at the University of Kansas School of Medicine on June 7, 1937. A few weeks prior to her graduation she wrote the folks with big news:

I received the honor of the next post graduate course in Obstetrics here! It’s given to only one out of every class. The girl is chosen as to her scholastic record, practical work, interest, and efficiency. It’s a new course and I’m only the 4th student. It doesn’t pay a great deal, but after you get out — there’s pretty good pay. It’s a four-month course, I’ll have to buy my colored uniforms, but Gee! I’m thrilled to death! . . .The first month I’m on day duty on the O.B. ward here, the next month on night duty and the last two months on outside O. B. calls, helping with home deliveries.

Home Deliveries in the Kansas City Slums

In his report to the Kansas Legislature1 H. R. Wahl, Dean of the K. U. School of Medicine, wrote of the outpatient department, “It is now providing almost 60,000 visits per year. It is from this department that maternity work in the homes of the poor is carried out. During the past year 711 babies were delivered in the various homes of the city.”

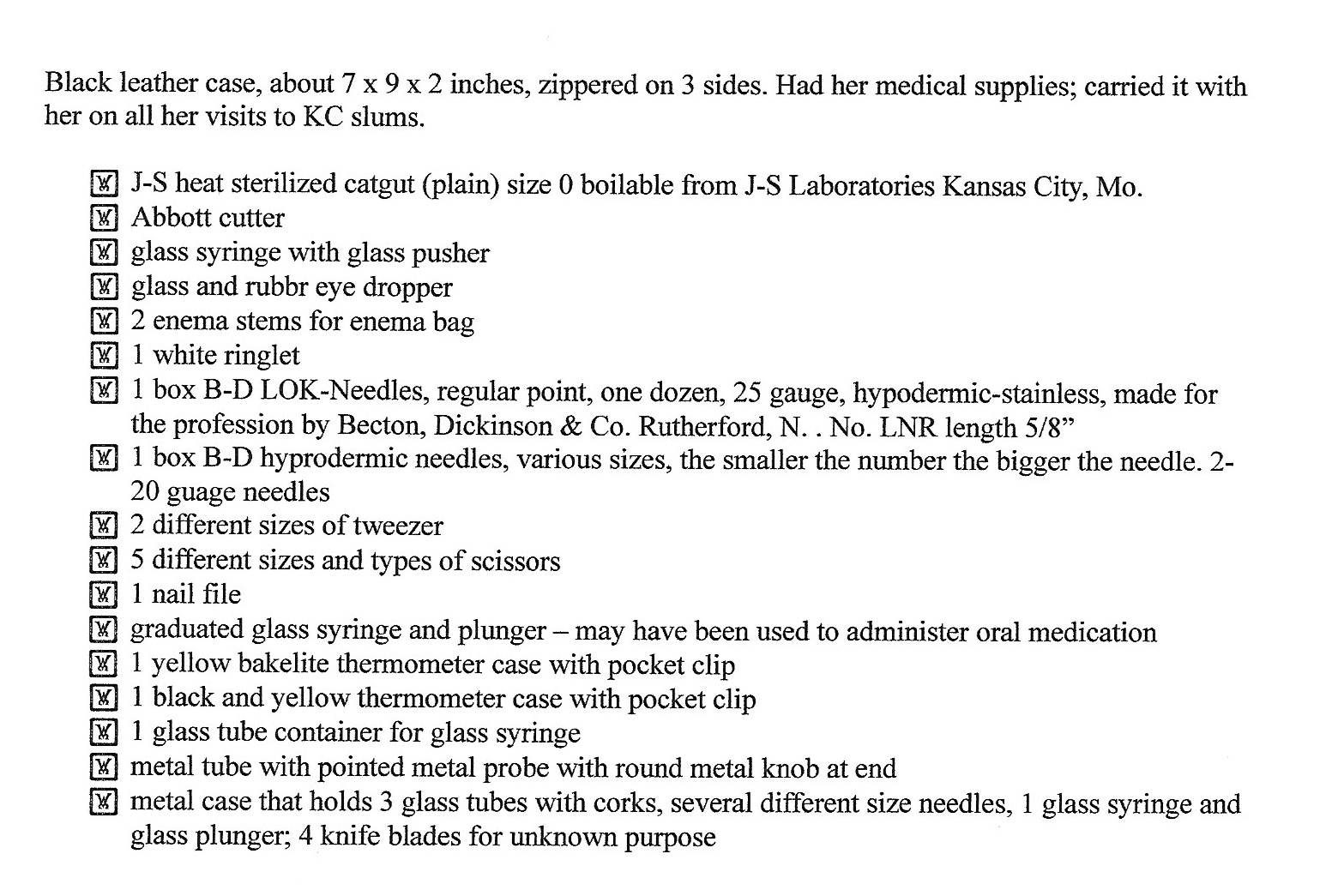

Ila completed her post-graduate training on October 16, 1937, and began working full time at the outpatient clinic. She carried her own medical bag with supplies specified by the clinic. See the list below.

In a recording of her life’s experiences Ila said, “We went into the slums in Kansas City and my job was to teach the medical students [residents] the sterile set-up.”

A sterile set-up is “a sterile surface on which to place sterile equipment that is considered free from microorganisms (Perry, cited in Doyle and McCutcheon, 2015). A sterile field is required for all invasive procedures to prevent the transfer of microorganisms and reduce the potential for surgical site infections. Sterile fields can be created . . . at the bedside using a prepackaged set of supplies for a sterile procedure or wound care.”2

But Ila’s job involved way more than sterile set-up. Once she confirmed that a woman was truly in labor (as opposed to false labor pains) Ila had to find the nearest telephone — usually the households were too poor to have their own phones — and call the clinic to have a medical student sent to the home. Then Ila had to assist with both the delivery and post-delivery care of the newborn and the mother. And if labor stopped Ila had to stay and help take care of other family members until labor resumed and the medical resident was called. To hear Ila’s full explanation of her tasks and see images of her go to: https://cindyentriken.com/2020/10/ilas-war-audio-recording-with-photographs-and-news-stories/

But after two years of being on call 24/7 for deliveries, Ila was exhausted and depressed. Exhausted because she wasn’t granted any time off during her two year stint, and because she rarely got a full night’s sleep.

And depressed because of the squalid living conditions she saw.

So, in mid-1940, after receiving two letters from the Red Cross inviting her to join the Army for a year of specialized training, Ila decided it was time for a change.

1Thirty-Fourth Biennial Report to the Kansas Legislature. July 1, 1930 – June 30, 1932.

2Glenda Rees Doyle and Jodie McCutcheon. Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care. 2015. Publisher: BCcampus.

Day 4 countdown — Out of the Frying Pan and into the Fire