Franklin W. Davis, Jr.1

why we observe memorial Day

This Memorial Day, set aside to remember the men and women who died in service to the United States,2 please join me in recognizing the service of Kansas native, Franklin W. Davis, Jr., a young man who died during WWII. Davis wasn’t famous – didn’t have any famous family members as far as I know. But his story is poignant and deserves to be told and remembered.

Finding the Letters

Ever since I started collecting war memorabilia in 2008, I’ve focused on ephemera, especially letters, maps, magazines, newspapers, and books. So I was very excited when in 2018 or ’19, I met a man at a local antiques fair who offered to sell me some WWII letters he’d acquired at an auction.

“There aren’t many, just three v-mails and four envelopes. The v-mails were written by a father to his son. All the v-mails are stamped ‘Return to Sender’ and all the envelopes are stamped ‘Missing in Action.'”

“Did you ever find out what happened to the young man,” I asked.

“Nope. I was going to but I ran out of time. You know how it is.”

I nodded. I did know how it was, and it still is that way for me today!

“Well, I want them. I’ll see if I can figure out what happened to him. I love doing research and trying to figure this kind of stuff out.”3

So I bought them.

the importance of mail in war time

Contact with home during any war is a significant means for keeping morale up. Nothing about war time is normal so hearing about the family, how the garden was progressing, who was dating whom, how the kids were doing in school — all that provided temporary relief from the chaos and horror of war.

As WWII progressed and the “distance between the front lines and home grew”4 post offices across the country were swamped with letters. Ships and planes were needed to transport supplies and troops so the U. S. Post Office, in conjunction with “the War and Navy Departments” developed a new way to send mail, i.e., V-mail. A v-mail letter was smaller, it could only be one page, and lighter weight than regular or even air mail.

“Letters to and from members of the Armed Forces overseas were microfilmed for transporting, then printed out for the recipient.”5 This new type of mail was officially begun on June 15, 1942.6

private first class franklin w. davis, jr.

Pfc. Franklin Davis, Jr., graduated from Williamsburg High School, Williamsburg, Kansas, in 1942 and was employed at the Sunflower ordnance works prior to entering the United States Army on February 8, 1943. His basic training was at Camp Young, a desert training center, and Camp Haan, an antiaircraft replacement training center, both in California. He was assigned to the 3207th Quartermaster Corps Service (Sv.) Company (Co.)7 and then sent to Fort Pierce, Florida, a training center for amphibious troops who were going to be part of the invasion of Normandy on D-Day. After Davis completed his training, he was sent to England, arriving there in February, 1944.

Letters From home

Franklin Davis, Jr.’s parents, Franklin, Sr., and Vera Davis, wrote their son weekly, and sometimes more often. Mr. Franklin used v-mail, while Mrs. Franklin preferred air mail. The only surviving v-mails, as far as I know, are from Davis, Sr., and are dated April 19, 1944, April 25, 1944, and May 1, 1944.

The family’s first notice that something was wrong was when Davis, Sr.’s April 19, 1944 v-mail was returned to him. The v-mail had been opened and stamped with the image you see below accompanied by the words “return to sender.”

I’ve reproduced the text of the April 19, 1944 v-mail below.

Dear Dub: Well we finally got another letter from you today. Air mail written on April 11th. it made pretty good time. I am sending this v-mail & your ma is sending you one by air mail to see which one gets there first. We went to Barton’;s sale today & did it rain? Simple poured on us all the way home but boy the old buick sure plowed right on home. We left the trailer up there as we bough some stuff & was afraid we could not pull it home in the rain. Jack D. bought a rubber ____ up. I got a ___ & two good cultivators for $7.20. I bought some horse collars and some pads & a barrel & some double tire repairs. Jack D. & Chuck P. went with us. Chuck bought a minnow siene. . . . Well Dub we got a check yesterday April 17th for $111.00 so I’m putting $44.00 of it in the Richmond Bank in your name & the same day you got another bond, I think you have 13 bonds now, so that totals $369.00 & you are to get $300.00 on your discharge so that equals $669.00 up to now so you ought to easily have your $1,000.00 by time you get out. Well Dub I’m sure tired so guess I’ll ring off & go to bed. Write soon. Be good. Dad

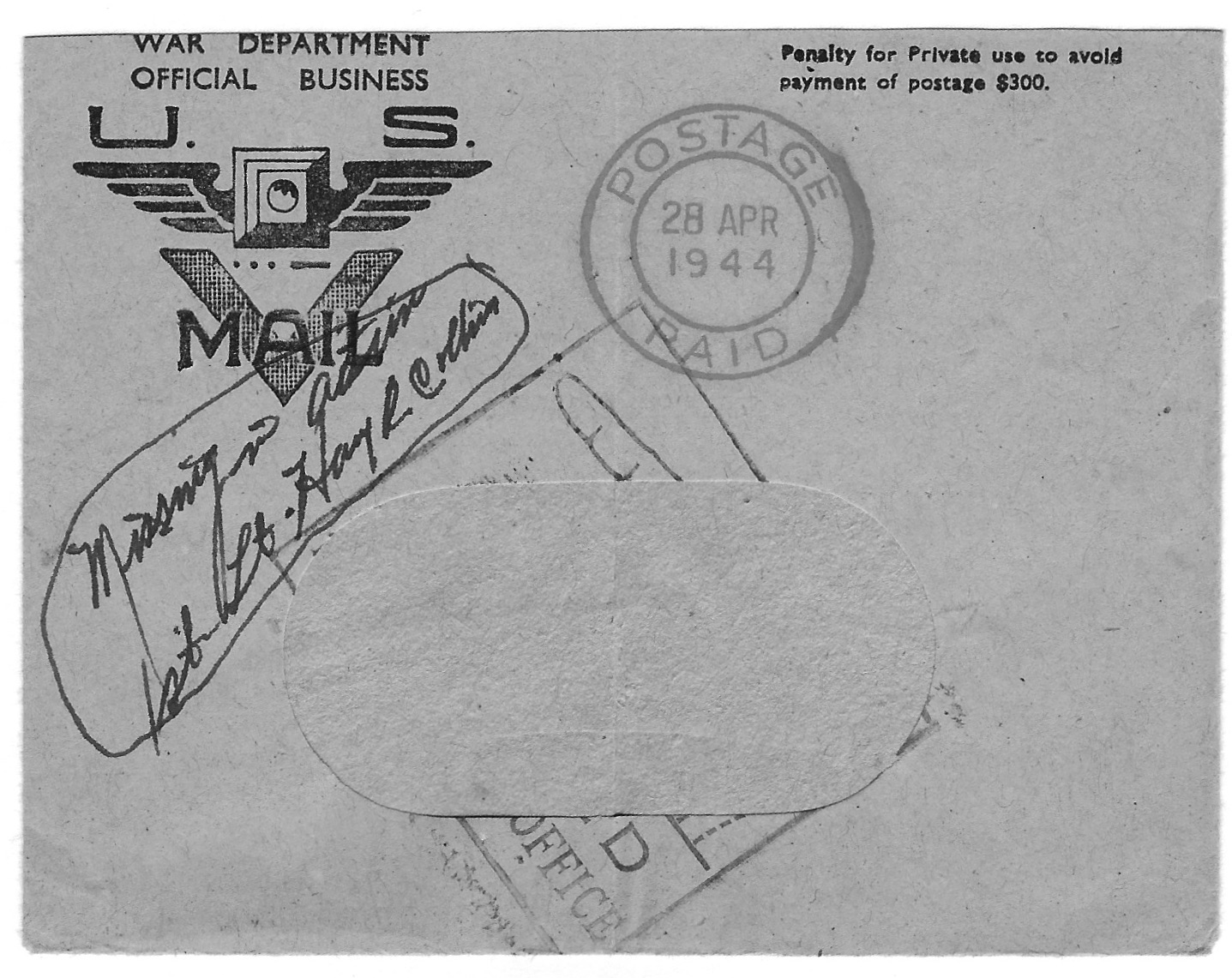

The original envelope for the v-mail above was apparently destroyed, so the v-mail was put into an official envelope of the War Department, and sent back to the family. I don’t have that envelope so I don’t know when the family first learned that Davis, Jr., was missing. But a subsequent v-mail returned to the family was in the envelope you see below. All four of the envelopes I purchased have the same hand-written note: “Missing in Action” signed by 1st Lt. Harry R. Collins.

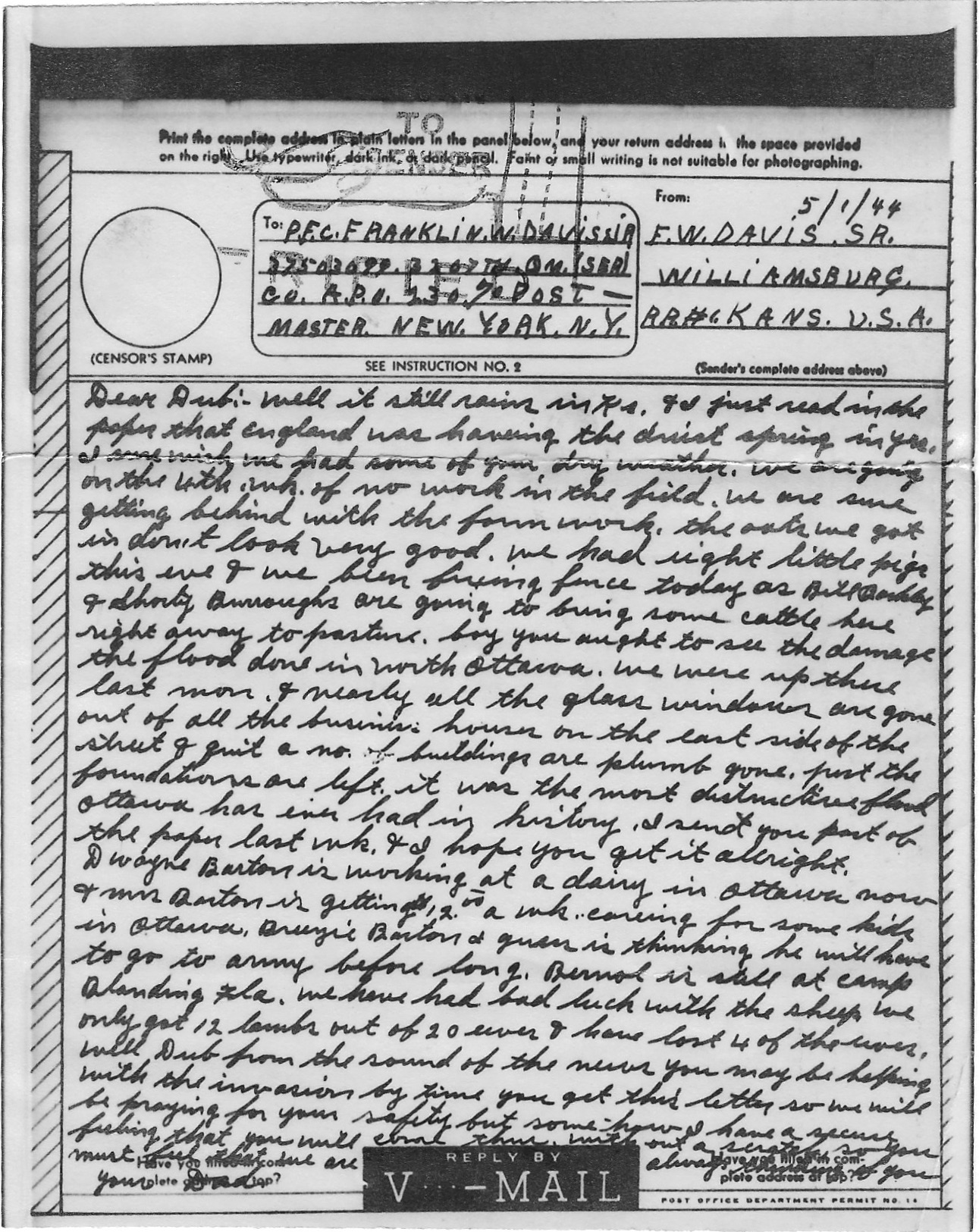

I have two more v-mails from Franklin, Sr., to his son dated April 25, 1944, and May 1, 1944. Both were newsy letters about the damaging rain and hail storms that hit the Ottawa, Kansas area in April and May, 1944, as well as news about friends and neighbors. Each letter was stamped with the pointing finger and the words, “Return to Sender.”

Below is a copy of Davis, Sr.’s v-mail. It’s the last few lines that are the most significant in this v-mail.

Well Dub from the sound of the news you may be helping with the invasion by time you get this letter so we will be praying for your safety but somehow I have a secure feeling that you will come thru without a scratch. So you must feel that we are always thinking of you. Your Dad

Learning about franklin Davis, Jr. and the v-mails

I had hoped, when I started doing research about Franklin Davis, Jr., that I’d discover he’d survived. Perhaps he’d been taken as a prisoner of war and the mail hadn’t caught up with him. Or maybe he’d been shipped out but later v-mails had reached him at his new assignment. I knew his folks lived in Franklin County, Kansas, based on the return address in the upper right-hand corner of the v-mail. So I contacted the Franklin County Historical Society (FCHS) to see what they knew. Within a day they had sent me what they had – a few grainy black and white photos of a young and smiling Franklin Davis, Jr., in his uniform, and a few brief news stories.

Once I compared the dates of the news stories with the dates of the v-mails I realized that Franklin was already dead when his father wrote the three v-mails I have. I was overwhelmed with grief, not just for Davis, Jr., but for his folks who continued to write v-mails full of plans for the future once “Dub” came home from the war.

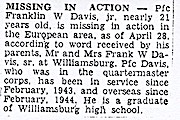

The first public announcement

On May 14, 1944, the Ottawa, Kansas, Herald published the following story:

But the family wasn’t told anything else. Three agonizing months passed before they finally learned the truth — that Davis and hundreds of other American servicemen had died during a secret military exercise code-named Exercise Tiger, off the coast of England.

Exercise Tiger

In preparation for D-Day, [from April 22 – 30, 1944,] the United States military held rehearsals involving 300 ships and approximately 30,000 soldiers. . . . The training exercises began in December 1943 and slowly escalated until they climaxed five months later with two full-scale rehearsals in late April and early May of 1944. . . . [T]he troops and equipment departed on the same ships and, for the most part, from the same ports that they would later leave from on June 6. To insure as accurate as possible preparation for the invasion the exercises where held on beaches that resembled the beaches of Normandy, which were code named Utah and Omaha. The military leaders held the exercises on Slapton Sands in England, which the Allies evacuated in the early part of 1944, for its resemblance to Omaha Beach.8

The secluded beach at Slapton Sands had been converted into a maze of mines, barbed wire and concrete obstacles. . . To give the soldiers a taste of the chaos of battle, the British Royal Navy planned to shell the beach with live fire until just moments before the American troops made their mock landing.9

In the early morning hours of April 28, 1944, an Allied fleet slinked toward the coast of southern England. Along with a lone British corvette, the flotilla included eight American tank landing ships, or LSTs, each one of them filled to the brim with soldiers from the U.S. Army’s VII Corps. In just five weeks, these same troops were scheduled to land in France as part of Operation Overlord, the Allies’ secret plan to invade Nazi-held Western Europe. 10

. . . [A]s the flotilla steamed through Devon’s Lyme Bay, it caught the attention of nine German “Schnellboote,” or “fast boats.” Known as “E-boats” to the Allies, these small, nimble raiders were outfitted with torpedoes and 40mm guns. Upon discovering that an Allied fleet was in the region, they immediately sped to intercept it.11

It was around 1:30 a.m. when the German E-boat attack began. As the eight American LSTs lumbered toward the coast, their crews were startled by an eruption of gunfire and the flash of tracer rounds in the night sky. “All hell broke loose,” one American sergeant remembered. The flotilla was caught completely off guard. British forces had been monitoring the approach of the E-boats, but due to an error, they were operating on a different radio frequency than the Americans. To make matters worse, the landing ships’ main escort, a British destroyer called the Scimitar, had sustained damage earlier in the evening and returned to port for repairs. When the shooting started, their only protection was a 200-foot corvette called the Azalea. . . . 12

The losses from the disaster eventually totaled 749 American sailors and soldiers killed and several hundred more injured, yet they were not immediately made public. With Operation Overlord still looming, the Allies temporarily kept the debacle under wraps out of fear that it might tip off the Germans. They even considered scrapping the Normandy invasion until the bodies of several officers with direct knowledge of the attack were recovered from the bay. The survivors, meanwhile, were threatened with court martial if they spoke of the tragedy to anyone.13

missing in action

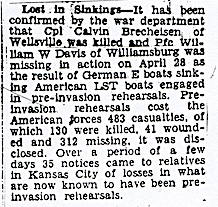

On August 7, 1944, the Ottawa Herald carried a small story announcing that a young man from Franklin County, Kansas, Cpl. Calvin Brecheisen, had died during pre-invasion rehearsals. But Franklin Davis, Jr., was still listed as missing in action. And now we know that the story inaccurately under-reported the number of troops killed in action by hundreds.

finally . . .

On August 14, 1944, the public learned what the family had only recently learned . . . that Franklin Davis, Jr. had been killed in action. The announcement, in the Ottawa Herald, read in part, “A telegram from the war department telling them that their son, Pfc Franklin W. Davis, Jr., 20, was killed in action in “the European area” was received Friday by Mr. and Mrs. Franklin W. Davis, . . .of Williamsburg. No details were given. [emphasis added] Pfc Davis was reported missing on April 28. Because Pfc Davis was in a quartermaster company with Cpl. Calvin Brechelsen of Wellsville who was killed at sea on April 28, members of the family believe the two died in the same engagement. . . .

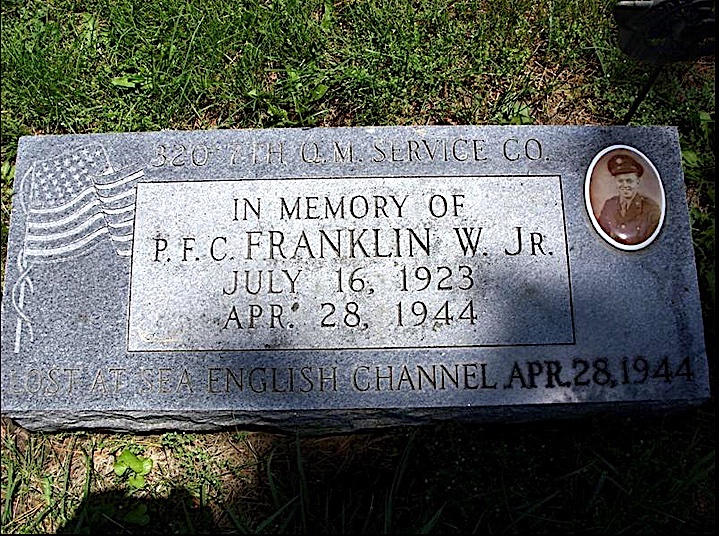

The memorial

Davis’ body was never recovered, but a memorial service was held for him at Mount Olivet Church, near Williamsburg, Kansas, in late October, 1944. A headstone for him were erected at the Mount Olivet Cemetery at Princeton, in Franklin County Kansas.

A white marble headstone was also installed at Arlington National Cemetery. Additionally, Davis’ name appears on the Roll of Honour Wall at the Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England, along with the names of 5,125 other Americans who died in the war but whose bodies were never recovered.14 You can see a photo of the wall with Davis’ name at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/45608036/franklin-weaver-davis.

___________

1photo courtesy of Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56289045/franklin-weaver-davis (accessed 5/31/2021)

2https://www.pbs.org/national-memorial-day-concert/memorial-day/history/ (accessed 5/27/2021)

3Sincere thanks to Ashley Brannon, Archives and Research Specialist, Old Depot Museum, Franklin County, Kansas, Historical Society, for hunting through their archives and giving me the information to reveal the story behind the v-mails.

4https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/victory-mail-introducing-v-mail/accelerated-service-shipping-v-mail (accessed 5/29/2021)

5https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/v-mail.pdf (accessed 5/30/2021)

6Ibid.

7The quartermaster service company provides military personnel for general labor. It is generally used as a “helping” unit to provide the additional labor personnel required by other units for the successful completion of their mission. The quartermaster service company may also be assigned independent missions, such as the operation of supply points, motor pools, laundries, etc. Personnel of the quartermaster service company may be used to furnish military labor or may e used to supervise civilian or prisoner of war labor. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc9469/m1/6/ (accessed 5/28/2021)

8http://www.wvculture.org/history/wvmemory/vets/exercisetiger.html (accessed 5/30/2021)

9https://www.history.com/news/d-days-deadly-dress-rehearsal (accessed 5/30/2021)

10Ibid.

11Ibid.

12Ibid.

13Ibid.

14http://www.roll-of-honour.com/Cambridgeshire/MadingleyUSACemetery.html (accessed 5/31/2021)

Enjoyed this one also! Ila’s war gave me a new picture of home,and people I knew as a child. Is it possible to meet you?

Hi, Paula. Although we haven’t met yet, I believe I know your folks. I’m so glad you8 enjoyed my story about Franklin Davis, Jr. and that you liked the book. I plan to do book readings and signing in various communities around Kansas in the coming months. Currently I’m wearing an enormous and heavy cast on my right foot and I have to use a knee roller. I can’t walk or drive and probably won’t be able to for several more weeks. Once I’m able to walk and drive I’ll post a schedule for public appearances. Perhaps we’ll meet at one of them. Best Regards.

Cindy, what a heartbreaking story. This is the first I have heard of this exercise tiger. Thanks for the information.

Thanks for your comment, LaDonna. Like you, I’d never heard about Exercise Tiger until I began doing research on Franklin Davis, Jr. It’s never too late to tell the truth and I’m thankful that with the help of the Franklin County Historical Society I could tell “the rest of the story” about Davis’ death.

Thank you for your research and documenting of Davis’ service to our country. The story of the exercises leading up to the invasion is one that I wasn’t familiar with and I appreciate your writing this compelling story of Davis, Exercise or Operation Tiger, and his family continuing efforts to communicate with him. Well done!

Thanks for your kind words, David. As you can probably tell, it’s important to me to provide the context along with the history. I think that helps in our understanding of the costs of war and humanity’s efforts to find ways to live together without killing each other. Best Regards.