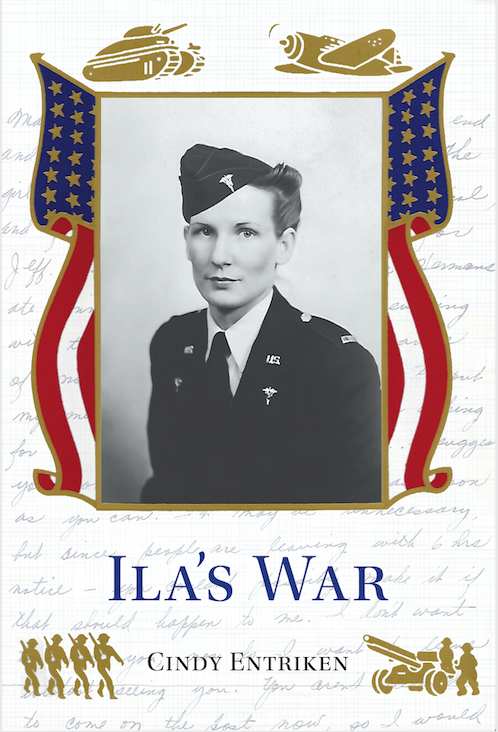

Ila’s War is a WWII memoir and the true story of the first 30 years of Ila Armsbury’s life. Hers is the story of an ordinary Kansan — an “every woman” — who aspired for more than the traditional roles of wife and mother. She wanted to travel, see the world and help others. But before she could do any of that, she had to convince her parents to let her leave the safety and confines of a small town in Kansas. After a year-long battle of wills, Ila, goes to nursing school and in December, 1940 enlists in the U. S. Army for one year. But Pearl Harbor changes everything.

You’ll want to read Ila’s War to learn about her family’s troubles, courtesy of her father . . .

- His arrest and trial for what we now call human trafficking

- A fight with the Ku Klux Klan

- The Jamaica Ginger scandal that poisoned over 50,000 American men and women and rocked the nation

And her experiences in Australia as a U. S. Army nurse

- Treating Marines from Guadalcanal

- Falling in love with an Army doctor

- Returning home as a patient in a VA hospital

You’ll root for Ila as she captures your heart with her humor, her desire to “tell it like it is”, and her persistence to live the life she dreamed.

Below is an excerpt from Ila’s War. The setting is Armsbury’s Cafe, owned by Ira Armsbury, in Lincoln, Kansas; the time, January, 1925.

*****

It was Friday night in mid-January, 1925 and Metta and I were working at the restaurant. I was glad to be up to my elbows in warm soapy water as I stood at the sink scraping pots. I preferred washing pots to being at home, caring for Eloise. At nine, my haunts were limited to the restaurant, home, school and church.

Metta was out front waiting on tables. Suddenly she burst into the kitchen through the swinging door, saying, “Daddy, there’s Klansmen in front of the restaurant with more marching this way and somebody’s calling your name — I don’t know who.”

Most Friday nights the Ku Klux Klan paraded right by, but this time, they stopped. Daddy turned from the huge black gas range and swore, but that didn’t bother me – I was used to it. A gigantic metal pot full of Daddy’s famous chili gave off to enticing odor of cumin and garlic and I could see beads of sweat on Daddy’s forehead. The griddle popped with the grease of hamburgers frying and I could smell onions already cooked and ready to be served up.

“They’ll just have to wait a minute. I’ve got food cooking here.” He turned back toward the stove as I quickly dried my chapped hands on my apron and walked out into the dining room. Like most Friday nights, the place was packed with Lincoln High School kids wolfing down hamburgers and cokes before the basketball game, and Catholic families enjoying the blue-plate special: Mother’s fried fish with a side of macaroni and cheese.

I hurried over to the steamy front window, wiped clear a peephole, and watched the Klansmen shuffle along in their pointy-hooded white robes. Metta was right behind me,“Move over,” she said. “ I want to see, too.”

Electric street lights and a waning crescent moon provided eerie light so the marchers looked like ghosts huddled in the street in front of the restaurant. Behind the kluxers, straight across the street from the restaurant the one-story limestone buildings gave off a dull white light while their big black windows looked like unblinking eyes. A few cars were parked diagonally at the curb on both sides of the street.

One of the Kluxers stood on the sidewalk about four feet from the front door. He was shuffling from one foot to the other, trying to keep warm, but probably nervous, too. Daddy could be a monster when he was angry. I could hear murmured voices coming from outside. The men stamped their feet on the frozen gravel street as they hopped around trying to ward off the bitter cold. One looked down at his boot and recoiled with disgust. Horse manure: not everything was frozen!

“Ira!” the man on the sidewalk called; I thought it was Mr. Hundertmark, the owner of The Hundertmark Store and a local KKK big-wig. Daddy came out of the kitchen and as he stomped by the lunch counter, untying his stained white apron, he said, “Metta, Ila, you stay in here.” He smacked the apron down on the counter and pushed through the front door, planting himself on the sidewalk with his hands on his hips. Even though Daddy had his back to us, I could tell he was furious. His arms were taut, his hands balled into fists, his head cocked to one side and his back straight as the yard-stick Mother used to paddle us with when we disobeyed.

Over to one side we could see an American flag and a big, wooden cross, each one held up by strong men in robes and hoods. The flag made a snapping sound as it flapped in the cold winter wind.

“Ira, we know you’re a loyal American . . .” said the man who’d called Daddy’s name a minute ago. Now I was sure it was Mr. Hundertmark.

“Damn right I am!”

“Now don’t get riled . . . nobody’s saying you aren’t. But it doesn’t look good doing business with someone who’s loyal to Rome and the papistry.”

We could see white-hooded heads bobbing up and down. “Porky Zink is as good an American as any of you — probably a damn sight better. And he’s my friend just like many of you are my friends.”

That was one thing about living in a small town — everybody knew everybody else and there was precious little you could hide from your neighbors. Why, every Monday morning when the clean laundry was put out you could see Klansmen’s white sheets with the holes cut for their heads, hanging on the clothes lines, and white pillowcases made into hoods with two eye holes hanging nearby.

“Porky has the best bread around. I’ve told you before and I’ll tell you again – I’m not switching bakers and that’s it.”

“It’s not just your baker that’s the problem. It’s serving breakfast to those Catholics on Sunday morning after they’ve gone to their church. Makes it look like you’re supporting Catholics over your own kind.”

“My own kind?”

“You know. It just doesn’t look good.”

I noticed suddenly that the restaurant was completely quiet behind me. Everybody sat still, some with forks halfway to their mouths.

A glass shattered, bursting the silence like a gunshot. Jack Donley, the son of a local farmer and a regular attendee at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shakily set the tray of glasses he was holding on the counter and stooped to pick up the shards. Jack, tall with dark hair and a quick smile, was a classmate of Wava’s and he helped us out on busy nights.

“So you want me to close on Sunday?” Daddy barked.

“No, no need to do that. Just don’t open up so early.”

“And who’s going to make up for my lost income? You fellas all planning to start eating your Sunday dinner at my restaurant?”

Silence.

”I didn’t think so. Well, I can tell you this. Folks who want a good breakfast at a decent price can always find it at Armsbury’s, and I’ll set my hours so I can get as many of ’em as I can because in my book a Catholic quarter and a Protestant quarter — they all spend the same.”

The Klansmen murmured to each other and moved off down Main Street.

Slowly, the restaurant came back to life. I got a broom and dustpan to help Jack. As we knelt by the mess of broken glass he kept his eyes turned from mine. “It’s okay, Jack. Daddy says they’re all just talk,” I said as I tried to re-assure him.

Daddy went back to the griddle, and I to the sink. “I told you, Ilie. Those Kluxers are just a bunch of blow-hards. Trying to interfere in a man’s own business when it’s none of theirs. Don’t you worry, honey. I can take care of myself and the restaurant, too.”

I was still shaken from everything I’d seen, but other than some talk nothing bad had happened so I figured Daddy was right and I went back to washing dirty pots and pans. The dishwater had cooled, but it felt good on my wrists. I put all my concentration into chipping melted cheese off of Mother’s big rectangular baking pan, trying to shut out the scene I’d just witnessed. Don’t think about it; I told myself. Just do your work and keep your eyes down. That was the Armsbury way, at least for us females.

Suddenly, shouting voices came from the dining room. “What’s going on here?” “For God’s sake, get out of here!” Then the sound of furniture tipping over and dishes breaking.

By the time Daddy and I got to the swinging kitchen door, two Klansmen had Jack Donley by the upper arms. He wriggled as they dragged him toward the front door of the restaurant. They lifted him clean off his feet, and with one great effort threw him through the big plate glass window that faced main street — with a sound like my whole world exploding – which it did.

You can’t imagine the fall-out. Wava had a conniption fit – she was mortified by the Klan’s attack at the restaurant.

“What will people think? You’ve shamed me in front of my friends.” Those were her exact words. She immediately dropped out of school at Lincoln, bought a one-way train ticket and went back to Lucas.

And as for Daddy? His rage was as cold as an arctic winter. He sold the restaurant – said he wasn’t going to let the Klan or anybody else tell him how to run his business or who to hire. He told Mother that as soon as school was out in May we were moving to Fairport, Kansas, about 75 miles west of Lincoln. And that’s exactly what we did.