In the spring of 1991 my 82-year-old grandmother decided it was time to start sorting through her accumulated treasures. Grammy had lived in the same house for 50 years, and as someone who’d grown up in stifling poverty, she’d saved everything. Her house was big, and every drawer, every closet, and every shelf of every room was packed. We agreed that we wouldn’t have time for her to tell me the history of every item as we culled. She was simply going to look at each memento and tell me whether it should go to someone in particular. My job was to put it in a paper grocery sack labeled with the person’s name.

The first sign that things weren’t going according to plan came with the twelve posters of Jesus’ disciples. “Now, Cindy,” she said, hauling them out, yellowed, brittle and peeling. “Remember these? I used them all those years I taught Sunday School. I thought you might like to have them.”

I had no use for torn, faded posters. When I suggested we toss them, Grammy gasped and looked at me with horror, her lips pursed in a thin, frowning line. “Why, I’ll do no such thing,” she said. “Someone else in the family will want them.” Despair settled over me like a cloud.

Replacing the posters on the closet shelf, she reached for a hatbox and opened it to reveal several women’s hats, long out of fashion. She picked up an old pale pink hat with tattered flowers, placed it on her curly white hair, and said, “When I was wearing this, I thought I was really something!” She sashayed over to the mirror above the dresser, like a model on a catwalk. After admiring herself, she removed the hat and replaced it in the box, carefully placing white tissue paper over it. “Cindy” she said, “would you like these?” I was afraid that if I refused she’d put the box back on the shelf, so I responded with a hearty “yes”.

I made better progress on receipts from the 1930s proving she’d paid her gas and electric bills. She agreed, reluctantly, to let them go. The waste basket slowly began to fill. A stack of old typed papers bound with string seemed a promising candidate for the trash, until she blew off the dust, saying, “These are the letters your great Auntie Ila wrote to Mother and Daddy during the war.”

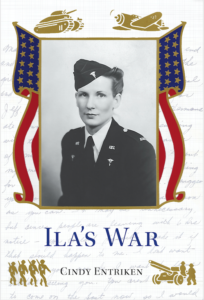

I put down whatever I had been holding. My heart beat faster; I flushed. I’d always known that Ila was an Army nurse in Australia during the war but I’d never heard any stories about her experiences and I’d certainly never known there was a written record. I wanted those letters. I knew from my own correspondence with Ila that she was candid, outspoken and a great story teller. I hoped her correspondence from the war would be just as salty and unvarnished.

I put down whatever I had been holding. My heart beat faster; I flushed. I’d always known that Ila was an Army nurse in Australia during the war but I’d never heard any stories about her experiences and I’d certainly never known there was a written record. I wanted those letters. I knew from my own correspondence with Ila that she was candid, outspoken and a great story teller. I hoped her correspondence from the war would be just as salty and unvarnished.

I asked Grammy if anyone had laid claim to the letters. She looked thoughtful for a minute. “No, no one has ever asked me about them,” she said looking me full in the face, her blue eyes intense.

I felt tension rising in me as I struggled to find the words to ask if I could have them. I hadn’t had perfect luck fending off what I didn’t want, and I worried that my earlier refusal to accept the Jesus posters might have angered her. I cleared my throat a couple of times, smiled, and asked if she’d consider giving them to me? “I don’t see why not, “ she said, looking thoughtful. “They haven’t been read since they were first received, and I’m sure nobody in the family even remembers them.”

So she gave me the letters, 450 pages of hand-written and typed missives from 1934, when Auntie Ila entered nursing school with her father’s grudging approval and meager financial assistance, until 1946 when she resigned from the U. S. Army after serving five and a half years when she’d only signed up for one.

My next blog: World War II Postcards